Patrick Ryoichi Nagatani (1945-)

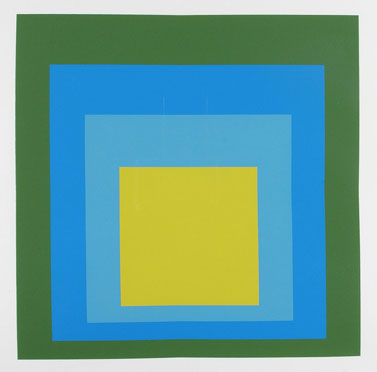

Akshobhya, 2010

Light jet chromogenic print, masking tape, mixed media, archival enhancing medium, 124 x 79 cm.

Gallery purchase, The Clarence A. Davis ’48 Endowed Fund for the Visual Arts

Akshobhya was a monk who vowed never to feel anger or disgust at another being. He was immovable in keeping this vow, and after long striving he became a Buddha.

Akshobhya is a heavenly Buddha who reigns over the eastern paradise, Abhirati. (Note that the eastern paradise is understood to be a state of mind, not a physical place.) Those who fulfill Akshobhya’s vow are reborn in Abhirati and cannot fall back into lower states of consciousness. In Buddhist iconography, Akshobhya usually is blue, sometimes gold. He is most often pictured touching the earth with his right hand. This is the earth-touching mudra, which is the gesture used by the historical Buddha when he asked the earth to bear witness to his enlightenment.

In the three-decade period beginning in 1978, Nagatani, like his works, has defied convention and labels. As an artist, he uses staged photography with carefully crafted props to become “a storyteller with images.” He has utilized masking tape as a form of tactile painting for a series Nagatani calls “Tape-estries.” “My approach today dwells in an ironic state of middle ground,” Nagatani explains. “Possibly one negative in our culture today is the attitude that things must be fact or fiction, good or bad, truth or lies, black or white, right or wrong, all or nothing, big or small, expensive or cheap, violent or docile, and so on. This kind of thinking leaves no room for magic and possibilities in creative endeavor that might be in the gray area or middle earth.” Influenced by his teacher and mentor from UCLA, Robert Heinecken, Nagatani in the mid-1970s chose to disregard “photographic truth” and to seek what he calls “the façade of representation.” Once a model maker for a company that made sets for movies and television, Nagatani applied those skills to his staged photography in the manner of a film director. Every object within the image was chosen to help tell a story and induce questions from the viewers about the veracity of the scene.Patrick Nagatani’s work has been exhibited internationally since 1976, including at the Art Institute of Boston , Museum of Photographic Arts , San Diego; and the Royal Photographic Society, Bath, England. Numerous books have featured his work including Seizing the Light: A History of Photography by Robert Hirsch (2000), and Photography by Barbara London and John Upton (1998). His work is in the collections of the Baltimore Museum of Art ; Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; Denver Art Museum International Center for Photography, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art ; and Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York. He has been the recipient of many awards including the Polaroid Fellowship and the NEA Visual Arts Fellowship. Currently a Professor of Art at the University of New Mexico, Nagatani lives in Albuquerque.

Tape-estries (1982 to 2013) Confessions of a Tapist

The process is like driving from Albuquerque to Los Angeles non-stop. It’s like being in shape and running ten miles. It’s like chanting. It’s like doing all the movements of Tai Chi the meditative way. It’s about finding a zone of no thought. Time passes and only my aching fingers and shoulders indicate how long I have been continuously painting with the tape. I relish the focus on details and to be lost in the quiet and minute parts of the whole. Decisions are mostly made as a reaction to the materials, the image and the emotive feel. Time is a factor. It must take long sessions to get to the zone. After each session there is another zonal journey. Clarity often comes after a long session. More things are revealed to me after each session. Magic is a goal. My entire day is shaped by solitude and what I believe is constructed beauty. I want magic in my life and work. Beauty is important. I relish the fact that the tape is an inexpensive and somewhat castaway art material. The Zen of the material and process moves me to a spiritual happiness.

I have often desired the overlay of sensory experience in my work. These pieces require looking from afar and getting in very close, both vantage points offer differing visual experience. The pieces are wonderful to touch. I’ve been in the zone off and on for over thirty years with this work. Time has no fixed position, it has been positive energy for me. It has left me no room or desire for negative creative existence. Most things seem to now have a place in the cosmic meaning of things. Especially in coping with getting older and dealing with cancer.

The taping process is obsessive. It is done with precision and ardor. Masking tape is a simple material. I use every variety of masking tape that is commonly available. The subtle color of the tape creates my range of hues for my “painting” palette. There are varying degrees of translucency and the amount of layers dictate a value shift. The tearing and cutting parodies a variety of “brush strokes.” The original surface images are large Chromogenic Lightjet photographs from a variety of sources that are often collaged and manipulated in Photoshop. These are cold mounted with Coda (two sided archival adhesive) to museum ragboard. The archival museum board is contact cemented to oak wood laminate and stretcher bars are wood glued for stability. Finally, the entire finish taped surface is multi-coated with Golden Acrylic Matte Medium of different strengths. Two final brush coatings of Golden Polymer Varnish with UVLS (Ultraviolet filters and stabilizers) are finally applied. Although masking tape is not considered an “archival” medium, the matte medium both seals the piece from oxidation and soaks through the masking tape for added adhesion. My “tapist” career started in 1982 and the pieces made at that time have lasted throughout the years. I believe that the pieces have a life of their own and will change very slowly in time, much like mummies from ancient Egypt have lasted through the centuries but nevertheless have changed. The work might be seen as an evolving entity with the spirit of permanence and impermanence interwoven into the materials used in the artistic process.

A perfect quote from Patricia J. Graham’s book, Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art 1600-2005, regarding artists influenced by using Buddhist imagery in Japan hits home to my thinking today. “All these artists turned to Buddhist imagery for intensely personal reasons, without regard for the whims of the art establishment, and developed distinctive styles for Buddhist subjects. They borrowed freely from Western art, philosophy and art materials in order to instill new life into traditional religious themes, and they completely absorb themselves into their work, which itself becomes a path of self-cultivation.”